By Al-bakri, a Member of a Prominent Spanish Arab Family Who Lived During the 11th Century.

| Ghana Empire غانا | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| c. 300–c. early 1200s | |||||||||||

The Ghana Empire at its greatest extent | |||||||||||

| Capital | Koumbi Saleh | ||||||||||

| Common languages | Fulfulde (Fula), Soninke, Arabic, Malinke, Mande | ||||||||||

| Religion | African traditional religion Later on Islam | ||||||||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||||||||

| Ghana | |||||||||||

| • 700 | Kaya Magan Cissé | ||||||||||

| • 790s | Majan Dyabe Cisse | ||||||||||

| • 1040–1062 | Ghana Bassi | ||||||||||

| • 1203–1235 | Soumaba Cisse | ||||||||||

| Historical era | 9th century-11th century | ||||||||||

| • Established | c. 300 | ||||||||||

| • Conversion to Islam | 1050 | ||||||||||

| • Conquered past Sosso/Submitted to the Mali Empire | c. early 1200s | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

| Today part of |

| ||||||||||

Wagadou (Arabic: غانا), unremarkably known as the Ghana Empire, was a West African empire based in the modernistic-24-hour interval southeast of Mauritania and western Mali that existed from c. 300 until c. 1100. The Ghana empire, sometimes also known as Awkar, was founded by the Soninke people and was based in the uppercase urban center of Koumbi Saleh.

Complex societies based on trans-Saharan trade in salt and gold had existed in the region for centuries at the time of the empire'southward formation.[1] The introduction of the camel to the western Sahara in the 3rd century CE served as a major goad for the transformative social changes that resulted in the empire's formation. By the fourth dimension of the Muslim conquest of North Africa in the 7th century the camel had changed the aboriginal, more irregular trade routes into a trade network running from Morocco to the Niger River. The Republic of ghana Empire grew rich from this increased trans-Saharan merchandise in gold and salt, allowing for larger urban centers to develop. The traffic furthermore encouraged territorial expansion to gain control over the dissimilar trade routes.

When Ghana'southward ruling dynasty began remains uncertain among historians. The first identifiable mention of the regal dynasty in written records was made past Muḥammad ibn Mūsā al-Khwārizmī in 830.[ii] Further information about the empire was provided past the accounts of Cordoban scholar Al-Bakri when he wrote nigh the region in the 11th century.

After centuries of prosperity, the empire would begin to pass up in the 2d millennium, and would finally become a vassal land of the rise Mali Empire at some point in the 13th century. Despite its collapse, the empire's influence can be felt in the establishment of numerous urban centers throughout its former territory. In 1957, the British colony of the Gold Coast under the leadership of Kwame Nkrumah named itself Ghana upon independence in honor and remembrance of the historic empire, although their geographic boundaries never overlapped.

Etymology [edit]

The word ghana means warrior or war chief and was the championship given to the rulers of the original kingdom whose Soninke name was Ouagadou. Kaya Maghan (lord of the gold) was some other title for these kings.[3]

History and accounts [edit]

Origin [edit]

Theorizing concerning the origins of Ghana has been dominated by disputes between ethnohistoric accounts and archaeological interpretations. The primeval discussions of its origins are plant in the Sudanese chronicles of Mahmud Kati and Abd al-Rahman as-Sadi. Co-ordinate to Kati'due south Tarikh al-Fettash in a section probably composed by the author around 1580, but citing the potency of the master judge of Messina, Ida al-Massini who lived somewhat before, twenty kings ruled Republic of ghana before the advent of the prophet Muhammad, and the empire extended until the century later on the prophet.[iv] In addressing the rulers' origin, the Tarikh al-Fettash provides 3 different opinions: that they were Soninke, Wangara (which are a Soninke group), or Sanhaja Berbers.

Al-Kati favored another interpretation in view of the fact that their genealogies linked them to this grouping, adding "What is sure is that they were not Soninke" (min al-Zawadi).[five] While the 16th-century versions of genealogies might have linked Ghana to the Sanhaja, earlier versions, for case equally reported by the 11th-century writer al-Idrisi and the 13th-century writer ibn Said, noted that rulers of Ghana in those days traced their descent from the association of the Prophet Muhammad either through his protector Abi Talib, or through his son-in-law Ali.[6] He says that 22 kings ruled before the Hijra and 22 afterwards.[seven]

While these early on views lead to many exotic interpretations of a foreign origin of Wagadu, these views are mostly disregarded past scholars. Levtzion and Spaulding, for instance, argue that al-Idrisi's testimony should be looked at very critically due to demonstrably gross miscalculations in geography and historical chronology, while they themselves associate Republic of ghana with the local Soninke.[eight] In addition, the archaeologist and historian Raymond Mauny argues that al-Kati'southward and al-Saadi's view of a strange origin cannot exist regarded equally reliable. He argues that the interpretations were based on the later presence (later Ghana's demise) of nomadic interlopers from Libya, on the assumption that they were the historic ruling degree, and that the writers did not adequately consider contemporary accounts such as those of Ya'qubi (872 CE), al-Masudi (c. 944 CE), Ibn Hawqal (c. 977 CE), and al-Biruni (c. 1036 CE), likewise as al-Bakri, all of whom draw the population and rulers of Republic of ghana as "negroes".[ix]

Trade routes of the Western Sahara c. 1000–1500. Goldfields are indicated past light brown shading: Bambuk, Bure, Lobi, and Akan.

Oral traditions [edit]

In the late 19th century, as French forces occupied the region in which aboriginal Ghana lay, colonial officials began collecting traditional accounts, including some manuscripts written in Arabic somewhat earlier in the century. Several such traditions were recorded and published. While there are variants, these traditions called the most aboriginal polity they knew of Wagadu, or the "identify of the Wago" the term current in the 19th century for the local nobility. The traditions described the kingdom as having been founded by a human being named Dinga, who came "from the east" (eastward.g., Aswan, Arab republic of egypt[10]), afterwards which he migrated to a variety of locations in western Sudan, in each identify leaving children by different wives. In order to attain power in his terminal location he had to impale a goblin, and so marry his daughters, who became the ancestors of the clans that were dominant in the region at the time of the recording of the faith. Upon Dinga'south death, his two sons Khine and Dyabe contested the kingship, and Dyabe was victorious, founding the kingdom.[11]

Theories concerning the foundation of Ghana [edit]

French colonial officials, notably Maurice Delafosse, whose works on West African history has been criticised by scholars such Charles Monteil, Robert Cornevin and others for being "unacceptable" and "too creative to be useful to historians" in relation to his falsification of W African genealogies,[12] [thirteen] [fourteen] [15] concluded that Ghana had been founded by the Berbers, a nomadic group originating from the Benue River and linked them to North African and Middle Eastern origins. While Delafosse produced a convoluted theory of an invasion by "Judeo-Syrians", which he linked to the Fulbe, others took the tradition at confront value and simply accustomed that nomads had ruled first.[sixteen] Raymond Mauny, synthesizing early archaeology, various traditions, and the Arabic materials in 1961 concluded that strange trade was vital to the empire'southward foundation.[17] More contempo work, for example by Nehemiah Levtzion, in his classic work published in 1973, sought to harmonize archeology, descriptive geographical sources written betwixt 830 and 1400 CE, the older traditions of the Tarikhs, from the 16th and 17th centuries and at terminal the traditions nerveless by French administrators. Levtzion concluded that local developments, stimulated by trade from North Africa, were crucial in the development of the state, and he tended to favor the more recently collected traditions over the other traditions in compiling his work.[eighteen] While there has non been much further study of either traditions or documents, archaeologists have added considerable nuance. Christopher Ehret observes that the proposed founding date of c. 300 CE fits very well with what is known nigh the Wagadu state's command of the trans-saharan gold trade.[19]

Contribution of archaeological research [edit]

Archaeological research was slow to enter the picture. While French archaeologists believed they had located the uppercase, Koumbi Saleh, in the 1920s when they located extensive stone ruins in the general area given in most sources for the capital letter, others argued that elaborate burials in the Niger Bend area may have been linked to the empire. It was not until 1969, when Patrick Munson excavated at Dhar Tichitt (the site of a civilisation associated with the ancient ancestors of the Soninke people) in modern-day Mauritania that the probability of an entirely local origin was raised.[20] The Dhar Tichitt site clearly reflected a circuitous culture present by 1600 BCE and had architectural and material culture elements that seemed to match the site at Koumbi Saleh. In more recent work in Dhar Tichitt, and then in Dhar Nema and Dhar Walata, it has get more than and more articulate that as the desert advanced, the Dhar Tichitt culture (which had abandoned its primeval site effectually 300 BCE, perchance because of pressure from desert nomads, but also because of increasing dehydration) moved southward into the still well-watered areas of northern Mali.[21] This at present seems the likely history of the circuitous society that can be documented at Koumbi-Saleh.

Malinke rule [edit]

In his brief overview of Sudanese history, Ibn Khaldun related that "the people of Mali outnumbered the peoples of the Sudan in their neighborhood and dominated the whole region." He went on to chronicle that they "vanquished the Susu and acquired all their possessions, both their aboriginal kingdom and that of Ghana."[22] According to a modernistic tradition, this resurgence of Mali was led by Sundiata Keita, the founder of Republic of mali and ruler of its core area of Kangaba. Delafosse assigned an capricious but widely accepted appointment of 1230 to the event.[23] This tradition states that Ghana Soumaba Cisse, at the time a vassal of the Sosso, rebelled with Kangaba and became part of a loose federation of Mande-speaking states. Subsequently Soumaoro's defeat at the Battle of Kirina in 1235 (a date over again assigned arbitrarily past Delafosse), the new rulers of Koumbi Saleh became permanent allies of the Mali Empire. As Mali became more powerful, Koumbi Saleh's role as an ally declined to that of a submissive state, and it became the client described in al-'Umari/al-Dukkali'south account of 1340.[24]

Imperial decline [edit]

Given the scattered nature of the Standard arabic sources and the ambiguity of the existing archaeological record, it is difficult to make up one's mind when and how Ghana declined and fell. The earliest descriptions of the empire are vague equally to its maximum extent, though according to al-Bakri, Republic of ghana had forced Awdaghost in the desert to accept its rule sometime between 970 and 1054.[25] Past al-Bakri'southward own fourth dimension, however, it was surrounded by powerful kingdoms, such as Sila. Ghana was combined in the kingdom of Mali in 1240, marking the cease of the Ghana Empire.

A tradition in historiography maintains that Ghana fell when it was sacked past the Almoravid movement in 1076–77, although Ghanaians resisted assault for a decade,[26] only this estimation has been questioned. Conrad and Fisher (1982) argued that the notion of whatever Almoravid military machine conquest at its core is merely perpetuated folklore, derived from a misinterpretation or naive reliance on Arabic sources.[27] Dierke Lange agrees but argues that this does non foreclose Almoravid political agitation, challenge that Ghana's demise owed much to the latter.[28] Sheryl 50. Burkhalter (1992) was skeptical of Conrad and Fisher'due south arguments and suggested that in that location were reasons to believe that at that place was conflict between the Almoravids and the empire of Republic of ghana.[29] [30] Furthermore, the archæology of ancient Ghana does not testify the signs of rapid modify and destruction that would be associated with any Almoravid-era military conquests.[31]

While there is no clear-cut account of a sack of Ghana in the gimmicky sources, the country certainly did convert to Islam, for al-Idrisi, whose account was written in 1154, has the country fully Muslim past that date. Ibn Khaldun, a fourteenth-century North African historian who read and cited both al-Bakri and al-Idrisi, reported an cryptic account of the country'south history as related to him by 'Uthman, a faqih of Ghana who took a pilgrimage to Mecca in 1394, according to which the power of Ghana waned as that of the "veiled people" grew through the Almoravid move.[32] Al-Idrisi's written report does non give any reason to believe that the Empire was smaller or weaker than information technology had been in the days of al-Bakri, 75 years earlier. In fact, he describes its uppercase equally "the greatest of all towns of the Sudan with respect to expanse, the most populous, and with the most extensive merchandise."[33] It is articulate, however, that Ghana was incorporated into the Mali Empire, according to a detailed account of al-'Umari, written around 1340 only based on testimony given to him by the "truthful and trustworthy" shaykh Abu Uthman Sa'id al-Dukkali, a long term resident. In al-'Umari/al-Dukkali'southward version, Ghana all the same retained its functions as a sort of kingdom within the empire, its ruler being the only one allowed to bear the title malik and "who is like a deputy unto him."[24]

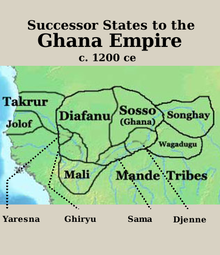

Sosso occupation and successor states [edit]

According to Ibn Khaldun, following Ghana'southward conversion, "the authority of the rulers of Ghana dwindled away and they were overcome past the Sosso...who subjugated and subdued them."[32] Some modern traditions identify the Susu as the Sosso, inhabitants of Kaniaga. According to much afterwards traditions, from the tardily nineteenth and twentieth centuries, Diara Kante took control of Koumbi Saleh and established the Diarisso Dynasty. His son, Soumaoro Kante, succeeded him and forced the people to pay him tribute. The Sosso also managed to annex the neighboring Mandinka country of Kangaba to the southward, where the important goldfields of Bure were located.

Economy [edit]

Virtually of the information virtually the economy of Republic of ghana comes from al-Bakri. Al-Bakri noted that merchants had to pay a i aureate dinar tax on imports of salt, and ii on exports of salt. Other products had fixed dues; al-Bakri mentioned both copper and "other goods." Imports probably included products such as textiles, ornaments and other materials. Many of the mitt-crafted leather goods found in onetime Morocco also had their origins in the empire.[34] Ibn Hawqal quotes the utilize of a cheque worth 42,000 dinars.[35] The main centre of trade was Koumbi Saleh. The king claimed as his own all nuggets of golden, and allowed other people to have just 'gilded dust'.[36] In addition to the influence exerted by the king in local regions, tribute was received from various tributary states and chiefdoms on the empire's periphery.[37] The introduction of the camel played a key role in Soninke success likewise, allowing products and appurtenances to exist transported much more than efficiently beyond the Sahara. These contributing factors all helped the empire remain powerful for some time, providing a rich and stable economy that was to concluding several centuries. The empire was also known to be a major educational hub.[ citation needed ]

Government [edit]

Testimony most ancient Ghana depended on how well tending the rex was to foreign travelers, from whom the majority of data on the empire comes. Islamic writers often commented on the social-political stability of the empire based on the seemingly just actions and grandeur of the rex. Al-Bakri, a Moorish nobleman living in Kingdom of spain questioned merchants who visited the empire in the 11th century and wrote of the male monarch:

He sits in audience or to hear grievances against officials in a domed pavilion around which stand 10 horses covered with gold-embroidered materials. Behind the king stand ten pages holding shields and swords decorated with gold, and on his right are the sons of the kings of his country wearing splendid garments and their hair plaited with gilded. The governor of the urban center sits on the ground before the king and around him are ministers seated likewise. At the door of the pavilion are dogs of excellent pedigree that inappreciably always leave the identify where the king is, guarding him. Around their necks they wear collars of gold and silverish studded with a number of balls of the aforementioned metals.[38]

Ghana appears to have had a central core region and was surrounded by vassal states. One of the primeval sources to depict Republic of ghana, al-Ya'qubi, writing in 889/90 (276 AH) says that "under his authority are a number of kings" which included Sama and 'Am (?) and so extended at least to the Niger River valley.[39] These "kings" were presumably the rulers of the territorial units oftentimes chosen kafu in Mandinka.

The Standard arabic sources are vague as to how the land was governed. Al-Bakri, far and abroad the nearly detailed i, mentions that the male monarch had officials (mazalim) who surrounded his throne when he gave justice, and these included the sons of the "kings of his country" which nosotros must presume are the aforementioned kings that al-Ya'qubi mentioned in his business relationship of nearly 200 years earlier. Al-Bakri's detailed geography of the region shows that in his day, or 1067/1068, Ghana was surrounded by independent kingdoms, and Sila, i of them located on the Senegal River, was "near a lucifer for the king of Ghana." Sama is the only such entity mentioned as a province, as it was in al-Ya'qubi's day.[40]

In al-Bakri's time, the rulers of Ghana had begun to comprise more than Muslims into government, including the treasurer, his interpreter, and "the majority of his officials."[38]

Influence of Islam [edit]

Modern scholars, particularly African Muslim scholars, have argued about the extent and chronology of the Ghana Empire. The African Arabist Abu-Abdullah Adelabu has claimed that some non-Muslim historians played down the territorial expansion of the Republic of ghana Empire in what he chosen an endeavour to understate the influence of Islam in former Ghana. In his work The Ghana Globe: A Pride For The Continent, Adelabu maintained that works of such Muslim historians and geographers in Europe as the Cordoban scholar Abu-Ubayd al-Bakri had been neglected to suit contrary views of not-Muslim Europeans.[41]

Adelabu claimed constant cold-shouldering of Ibn Yasin's Geography of the Maliki school, in which he gave a comprehensive account of social and religious activities in the Ghana Empire. He asserted that there has been a well-attested compositional bias in the documentation of Ghana history, especially by European historians on topics related to Islam and ancient Muslim societies. Adelabu wrote that "the early Muslim documentaries including Ibn Yasin'south revelations on ancient African major centers of Muslim culture crossing the Maghreb and the Sahel to Timbuktu and downward to Bonoman had not just presented researchers in the field of African History with solutions to the scarcity of written sources in large parts of sub-Saharan Africa, it consolidated confidence in techniques of oral history, historical linguistics and archaeology for authentic Islamic traditions in Africa".[42] [43]

Koumbi Saleh [edit]

The empire's upper-case letter is believed to have been at Koumbi Saleh on the rim of the Sahara desert.[44] According to the clarification of the town left by Al-Bakri in 1067/1068, the majuscule actually consisted of two cities 10 kilometres (6 mi) apart but "between these two towns are continuous habitations", then that they might be said to have merged into ane.[38]

El-Ghaba [edit]

Co-ordinate to al-Bakri, the major part of the urban center was called El-Ghaba and was the residence of the king. It was protected by a rock wall and functioned as the royal and spiritual capital of the Empire. It contained a sacred grove of trees in which priests lived. Information technology besides independent the rex's palace, the grandest construction in the city, surrounded by other "domed buildings". There was also one mosque for visiting Muslim officials.[38] (El-Ghaba, coincidentally or not, means "The Forest" in Arabic.)

Muslim commune [edit]

The name of the other department of the city is not recorded. In the vicinity were wells with fresh h2o, used to abound vegetables. It was inhabited nearly entirely by Muslims, who had with twelve mosques, ane of which was designated for Fri prayers, and had a full grouping of scholars, scribes and Islamic jurists. Considering the majority of these Muslims were merchants, this office of the city was probably its primary business organization district.[45] It is likely that these inhabitants were largely black Muslims known every bit the Wangara and are today known as Fulbe/Fulani and Jakhanke. The separate and autonomous towns outside of the main governmental center is a well-known practice used by the Fulbe and Jakhanke Muslims throughout history.

Archaeology [edit]

The Western Nile according to al-Bakri (1068)

A 17th-century chronicle written in Timbuktu, the Tarikh al-fattash, gave the name of the capital every bit "Koumbi".[four] Beginning in the 1920s, French archaeologists excavated the site of Koumbi Saleh, although at that place have always been controversies about the location of Ghana's capital and whether Koumbi Saleh is the same town as the i described past al-Bakri. The site was excavated in 1949–50 by Paul Thomassey and Raymond Mauny[46] and by another French team in 1975–81.[47] The remains of Koumbi Saleh are impressive, fifty-fifty if the remains of the royal boondocks, with its big palace and burial mounds, accept not been located. Another trouble for archeology is that al-Idrisi, a twelfth-century author, described Ghana'southward royal city as lying on a riverbank, a river he chosen the "Nile" following the geographic custom of his day of confusing the Niger and Senegal Rivers, which do non encounter, as forming a single river often called the "Nile of the Blacks". Whether al-Idrisi was referring to a new and subsequently capital letter located elsewhere, or whether there was defoliation or corruption in his text is unclear. Nevertheless, he does state that the royal palace he knew was built in 510 AH (1116–1117 CE), suggesting that information technology was a newer town, rebuilt closer to the Niger than Koumbi Saleh.[33]

List of rulers [edit]

Soninke rulers ("Ghanas") of the Cisse dynasty [edit]

- Mayan Dyabe Cisse: circa 790s

- Bassi: 1040–1062

- Tunka Manin: 1062–1076

Almoravid occupation [edit]

- Abu Bakr ibn Umar: 1076–1087

Sosso rulers [edit]

- Kambine Diaresso : 1087-1090

- Suleiman: 1090-1100

- Bannu Bubu: 1100-1120

- Majan Wagadou: 1120-1130

- Gane: 1130-1140

- Musa: 1140-1160

- B irama: 1160-1180

Rulers during Kaniaga occupation [edit]

- Diara Kante: 1180-1202

- Soumaba Cisse as vassal of Soumaoro: 1203–1235

Ghanas of Wagadou Tributary [edit]

- Soumaba Cisse as ally of Sundjata Keita: 1235–1240

Come across as well [edit]

- History of the Soninke people

- Islam in Africa

References [edit]

- ^ Burr, J. Millard and Robert O. Collins, Darfur: The Long Road to Disaster, Markus Wiener Publishers: Princeton, 2006, ISBN 1-55876-405-4, pp. 6–7.

- ^ al-Kuwarizmi in Levtzion and Hopkins, Corpus, p. 7.

- ^

- ^ a b Houdas & Delafosse 1913, p. 76.

- ^ Houdas & Delafosse 1913, p. 78, translation from Levtzion 1973, p. 19

- ^ al-Idrisi in Levtzion and Hopkins, Corpus, p. 109, and ibn Sa'id, p. 186.

- ^ Hunwick 2003, p. thirteen and annotation 5.

- ^ Levtzion & Spaulding 2003, p. 27.

- ^ Mauny 1954, p. 204.

- ^ Alexander, Leslie M.; Jr, Walter C. Rucker (9 February 2010). Encyclopedia of African American History [3 volumes]. ABC-CLIO. ISBN9781851097746 . Retrieved 13 September 2018 – via Google Books.

- ^ Levtzion 1973, pp. 16–17.

- ^ Monteil, Charles (1966). "Fin de siècle à Médine (1898-1899)". Bulletin de l'IFAN. série B. 28 (1–two): 166.

- ^ Vidal, Jules (1924). "La légende officielle de Soundiata, fondateur de l'Empire manding". Bulletin du Comité d'Études Historiques et Scientifiques de l'AOF. viii (2): 317–328.

- ^ African Studies Association, History in Africa, Vol. eleven, African Studies Association, 1984, University of Michigan, pp. 42-51.

- ^ Cornevin, Robert, Histoire de 50'Africa, Tome I: des origines au XVIe siècle (Paris, 1962), 347-48 (reference to Delafosse in Haut-Sénégal-Niger vol. 1, pp. 256-257)

- ^ Delafosse 1912, pp. 215–226 Vol. one.

- ^ Mauny 1961, pp. 72–74, 508–511.

- ^ Levtzion 1973, pp. 8–17.

- ^ Ehret 2016, p. 300.

- ^ Munson 1980.

- ^ Kevin McDonald, Robert Vernet, Dorian Fuller and James Woodhouse, "New Light on the Tichitt Tradition" A Preliminary Report on Survey and Earthworks at Dhar Nema," pp. 78–fourscore.

- ^ ibn Khaldun in Levtzion and Hopkins, Corpus, p. 333.

- ^ Delafosse 1912, p. 291 Vol. 1.

- ^ a b al-'Umari in Levtzion and Hopkins, eds. and trans. Corpus, p. 262.

- ^ al-Bakri in Levtzion and Hopkins, eds. and trans. Corpus, p. 73.

- ^ For case, Levtzion, Ghana and Mali, pp. 44–48.

- ^ Masonen & Fisher 1996.

- ^ Lange 1996, pp. 122–159.

- ^ "Listening for Silences in Almoravid History: Some other Reading of "The Conquest that Never Was" Camilo Gómez-Rivas

- ^ "Law and the Islamization of Kingdom of morocco under the Almoravids" Camilo Gómez-Rivas

- ^ Insoll 2003, p. 230.

- ^ a b ibn Khaldun in Levtzion and Hopkins, eds. and trans. Corpus, p. 333.

- ^ a b al-Idrisi in Levtzion and Hopkins, Corpus, pp. 109–110.

- ^ Chu, Daniel and Skinner, Elliot. A Glorious Age in Africa, 1st ed. Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1965.

- ^ Krätli, Graziano; Lydon, Ghislaine (2011). The Trans-Saharan Book Trade: Manuscript Culture, Standard arabic Literacy and Intellectual History in Muslim Africa. Brill Publishers. ISBN9789004187429.

- ^ al-Bakri in Levtzion and Hopkins, eds. and trans. Corpus, p. 81.

- ^ "The Story of Africa- BBC World Service". www.bbc.co.uk . Retrieved 13 September 2018.

- ^ a b c d al-Bakri (1067) in Levtzion and Hopkins, Corpus, p. fourscore.

- ^ al-Ya'qubi in Levtzion and Hopkins, eds. and trans. Corpus, p. 21.

- ^ al-Bakri in Levtzion and Hopkins, eds. and trans., Corpus, pp. 77–83.

- ^ Al-Bakri Siffah Iftiqiyyah Wal-Maghrib (Description Of Africa and The Maghreb), D. Slan, Algeria, 1857, p. 158.

- ^ Dr. Hussein Mouanes Atlas Taarikh Al-Islam (Atlas of Islamic History), p. 372.

- ^ "Akan of Ghana and their ancient beliefs" past Eva L.R. Meyerowitz, Faber and Faber Express.1958. 24 Russel Square London

- ^ Levtzion 1973, pp. 22–26.

- ^ al-Bakri, 1067 in Levtzion and Hopkins, Corpus, pp. 79–80.

- ^ Thomassey & Mauny 1951.

- ^ Berthier 1997.

Sources [edit]

- Berthier, Sophie (1997), Recherches archéologiques sur la capitale de l'empire de Ghana: Etude d'un secteur, d'habitat à Koumbi Saleh, Mauritanie: Campagnes Ii-Three-IV-V (1975–1976)-(1980–1981), British Archaeological Reports 680, Cambridge Monographs in African Archaeology 41, Oxford: Archaeopress, ISBN978-0-86054-868-3 .

- Delafosse, Maurice (1912), Haut-Sénégal-Niger: Le Pays, les Peuples, les Langues; l'Histoire; les Civilizations. 3 Vols (in French), Paris: Émile Larose . Gallica: Volume i, Le Pays, les Peuples, les Langues; Volume 2, L'Histoire; Volume 3, Les Civilisations.

- Ehret, Christopher (2016), The Civilizations of Africa: A History to 1800, Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press

- Houdas, Octave; Delafosse, Maurice, eds. (1913), Tarikh el-fettach par Mahmoūd Kāti et 50'un de ses petit fils (ii Vols.), Paris: Ernest Leroux . Book one is the Standard arabic text, Book 2 is a translation into French. Reprinted by Maisonneuve in 1964 and 1981. The French text is also available from Aluka but requires a subscription.

- Hunwick, John O. (2003), Timbuktu and the Songhay Empire: Al-Sadi's Tarikh al-Sudan downwardly to 1613 and other contemporary documents, Leiden: Brill, ISBN978-90-04-12560-5 . Reprint of the 1999 edition with corrections.

- Insoll, Timothy (2003), Archaeology of Islam in Sub-saharan Africa, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBN978-0-521-65702-0 .

- Lange, Dierk (1996), "The Almoravid expansion and the downfall of Ghana", Der Islam, 73 (2): 313–51, doi:10.1515/islm.1996.73.two.313, S2CID 162370098 . Reprinted in Lange 2004, pp. 455–493.

- Lange, Dierk (2004), Ancient Kingdoms of West Africa, Dettelbach, Germany: J. H. Röll, ISBN978-3-89754-115-3 .

- Levtzion, Nehemia (1973), Ancient Republic of ghana and Mali, London: Methuen, ISBN978-0-8419-0431-6 . Reprinted with additions 1980.

- Levtzion, Nehemia; Hopkins, John F. P. eds. and trans. (2000), Corpus of Early Arabic Sources for West Africa, New York, NY: Marcus Weiner, ISBN978-one-55876-241-i . Offset published in 1981 past Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-22422-5.

- Levtzion, Nehemia; Spaulding, Jay (2003), Medieval Due west Africa: Views from Arab Scholars and Merchants, Princeton NJ: Markus Wiener, ISBN978-1-55876-305-0 . Excerpts from Levtzion & Hopkins 1981. Includes an extended introduction.

- Masonen, Pekka; Fisher, Humphrey J. (1996), "Not quite Venus from the waves: The Almoravid conquest of Ghana in the modern historiography of Western Africa" (PDF), History in Africa, 23: 197–232, doi:10.2307/3171941, JSTOR 3171941 .

- Mauny, Raymond A. (1954), "The question of Ghana", Periodical of the International African Institute, 24 (3): 200–213, doi:ten.2307/1156424, JSTOR 1156424 .

- Mauny, Raymond (1961), Tableau géographique de 50'ouest africain au moyen age, d'après les sources écrites, la tradition et l'archéologie, Dakar: Institut français d'Afrique Noire .

- Munson, Patrick J. (1980), "Archeology and the prehistoric origins of the Ghana Empire", The Journal of African History, 21 (4): 457–466, doi:10.1017/s0021853700018685, JSTOR 182004 .

- Thomassey, Paul; Mauny, Raymond (1951), "Campagne de fouilles à Koumbi Saleh", Bulletin de I'lnstitut Français de I'Afrique Noire (B) (in French), thirteen: 438–462, archived from the original on 2011-07-26 . Includes a plan of the site.

Farther reading [edit]

- Conrad, David C.; Fisher, Humphrey J. (1982), "The conquest that never was: Ghana and the Almoravids, 1076. I. The external Arabic sources", History in Africa, 9: 21–59, doi:10.2307/3171598, JSTOR 3171598 .

- Conrad, David C.; Fisher, Humphrey J. (1983), "The conquest that never was: Ghana and the Almoravids, 1076. II. The local oral sources", History in Africa, 10: 53–78, doi:x.2307/3171690, JSTOR 3171690 .

- Cornevin, Robert (1965), "Ghana", Encyclopaedia of Islam Volume 2 (2nd ed.), Leiden: Brill, pp. 1001–2, ISBN978-ninety-04-07026-4 .

- Cuoq, Joseph M., translator and editor (1975), Recueil des sources arabes concernant 50'Afrique occidentale du VIIIe au XVIe siècle (Bilād al-Sūdān) (in French), Paris: Éditions du Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique . Reprinted in 1985 with corrections and additional texts, ISBN 2-222-01718-ane. Like to Levtzion and Hopkins, 1981 & 2000.

- Masonen, Pekka (2000), The Negroland revisited: Discovery and invention of the Sudanese middle ages, Helsinki: Finnish University of Science and Letters, pp. 519–23, ISBN978-951-41-0886-0 .

- Mauny, Raymond (1971), "The Western Sudan", in Shinnie, P.L. (ed.), The African Iron age, Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 66–87, ISBN978-0-19-813158-8 .

- Monteil, Charles (1954), "La légende du Ouagadou et l'origine des Soninke", Mélanges Ethnologiques, Dakar: Mémoire de fifty'Found Français d'Afrique Noire 23, pp. 359–408 .

External links [edit]

- Ghana Empire - World History Encyclopedia

- African Kingdoms | Ghana

- Empires of due west Sudan

- Kingdom of Ghana, Principal Source Documents

- Ancient Ghana — BBC World Service

Coordinates: fifteen°forty′N 8°00′W / fifteen.667°N 8.000°W / 15.667; -8.000

freemanthrealthen.blogspot.com

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ghana_Empire

0 Response to "By Al-bakri, a Member of a Prominent Spanish Arab Family Who Lived During the 11th Century."

Post a Comment